Airline Carry-on Baggage

I was working with a design team at an airline. The airline was experiencing low on-time departure metrics. The stakeholders assumed that if they reduced the number of carry-on bags, people would get settled in their seats faster, and then on-time departure metrics would rise. These stakeholders also assumed that on-time departure was a metric that was important to the different thinking-styles of passengers. But the stakeholders weren’t aware that they held these assumptions.

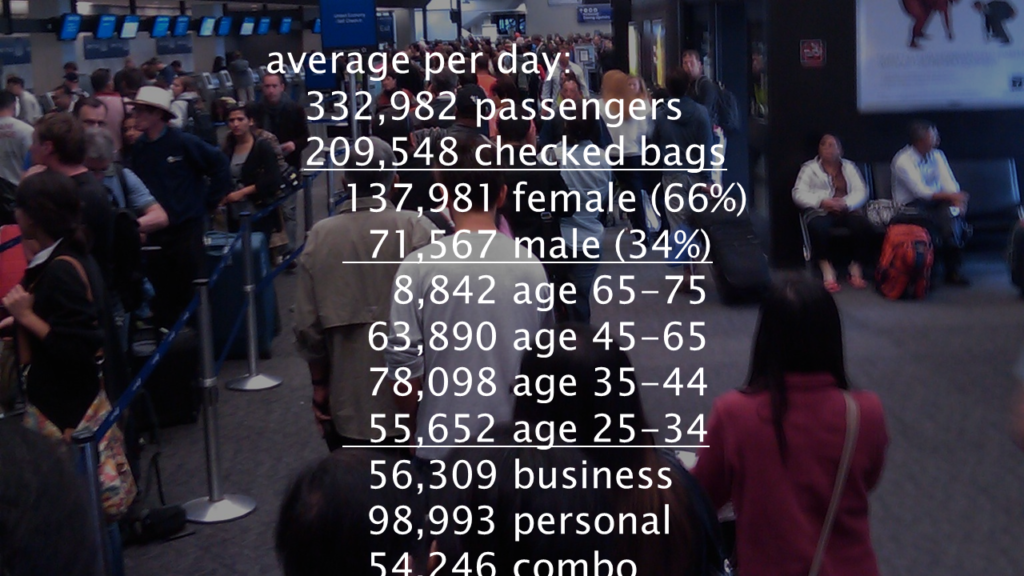

The stakeholders tasked the design team with designing a way to get more people to check their luggage rather than carry it on. So the team decided to begin with research. They asked other airline teams for existing data about checking bags. They received quantitative data sets, such as this one.

On Day X: 332,982 passengers who checked 209,548 bags:

- 137,981 were female (66%)

- 71,567 were male (34%)

- Age range 65–75 checked 8,842 bags

- Age range 45–64 checked 63,890 bags

- Age range 35–44 checked 78,098 bags

- Age range 25–34 checked 55,652 bags

- 56,309 of the bags were checked at curbside

- 98,993 of the bags were checked at the kiosks inside the airports

- 54,246 of the bags were checked at the counter by an agent

I had been working with this team for several months already, helping them connect with better awareness of their design decisions. When they received this quantitative data about checked baggage, I immediately noticed the way the data was broken down. Somewhere along the line, the other airline team supplying this data made decisions about what information was considered important and relevant, but I failed to see the connection to passengers’ real thinking. I asked the team: what’s wrong with this picture?

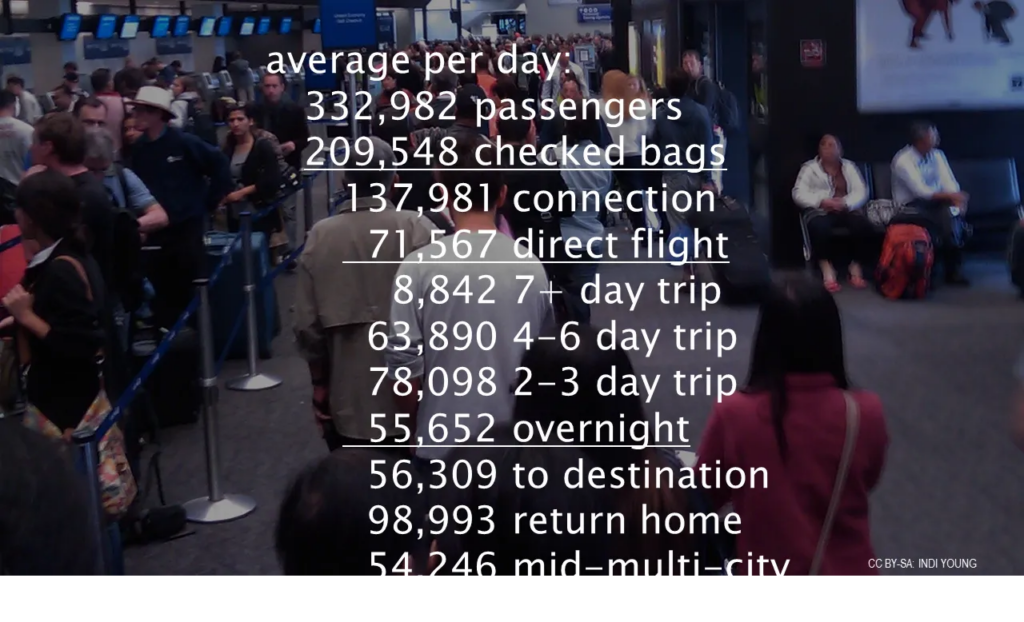

They considered what they were seeing and responded, “The data set is broken down in a conventional way: gender, age, etc. The gender they show is only binary. The info is only drawn from ticket data. This breakdown may not have anything to do with checking a bag.” Good! I asked them what they would do in place of this. Here’s what I got back.

On Day X: 332,982 passengers who checked 209,548 bags

- 137,981 had a connecting flight

- 71,567 had direct flights

- 8,842 of the bags were from passengers with a 7+ day trip

- 63,890 of the bags were from passengers with a 4–6 day trip

- 78,098 of the bags were from passengers with a 2–3 day trip

- 55,652 of the bags were from passengers with an overnight trip

- 56,309 of the bags were checked on the way to the destination

- 98,993 of the bags were checked on the return home

- 54,246 of the bags were checked in the middle of a multi-city trip

A member of the team told me, “When I have a connection, I’m less likely to want to drag a roll-aboard along with me through the airport. And when I take a longer trip, I pack more, therefore I’m likely to need a bigger suitcase and check it in. Also, I’m more likely to check my bag on my return home because if it gets lost, I still have clothes at home to wear. I don’t have to go buy replacements like I would if my bags were lost on the way to my destination.” You may be thinking these explanations don’t match the data, but it’s trickier than that. Notice all the “I’s” in there. It only represents their own experiences and thinking. This is research theater.

Instead, I helped the team define a study to understand what went through people’s minds the last few times they took bags to the airport. We did listening sessions to carefully collect other perspectives. It took us a month (10 hours a week, five researchers) to collect and analyze this qualitative data. We used a two-step analysis method rather than risk curating the patterns according to our own unconscious bias. And guess what? The results had nothing to do with gender or age, nor did they have anything to do with connections, the length of the trip, or whether a person was going out or coming back. Here are the four thinking-style patterns we found.

Thinking styles discovered we so far:

“Never Again:” I carried on my bag because I worry I will lose a checked bag; I assume my checked bag will be thrashed again; I wonder what the white powder was on my bag.

“My Precious:” I carried on my bag because I keep my expensive medical device with me; I make sure my guitar is not damaged in baggage; I carry on my computer & camera so they are not stolen.

“Had To:” I checked my bag because I check things I can’t get through security, like beer from Belgium; I check my bulky gift, my poster, my scuba gear that won’t fit in the overhead bin.

“Hassle Drag:” I check my bag because I avoid rolling the bag through connecting airports; I need to keep track of my kids, not my roll-aboard; I realize picking up the checked bag only adds 5 minutes.

This work gave us deeper insight into what was truly happening. It also reminded us that the approaches were contextually dependent, so any one person may change their thinking style regarding bags from flight to flight. That’s an important point when it comes to creating baggage services that vary in tone and support for the various thinking styles.

The airline started out with the instinct to be punitive. They figured the stubborn passengers who were delaying the on-time departures needed to be forced into a new behavior. They had wanted to make extra charges for baggage brought on board, paying special attention to the demographics that tended to bring bags on board. But correlation of the quantitative data turned out not to be the cause of behavior. Instead, these thinking styles helped the design team take the airline in new, more human directions.

Idea 1: All the Amazing Precious Things We’ve Carried in Our Overhead Bins

The team can write stories as interest pieces about some fabulous real stories. Each story can feature one passenger and their precious carry-on piece. They are written in a tone that is aimed at the My Precious thinking style, but will be of interest to the others. The stories celebrate the passenger and their item, and will help readers associate the overhead bins with precious items. The stories also start to shift the thinking of the airline employees.

Idea 2: Lost Baggage Personal Buyer

In the case of lost baggage, the team might create a new service that helps passengers avoid the Never Again mindset. There are several scenarios which this service can cover, including the situation where the passenger does not have time to get supplies and clothes to cover the days before they receive their luggage. The service would find stores close to where a passenger is staying to buy replacement items with pre-arranged store vouchers. In foreign cities, the service could even provide videos made in the local language to help passengers interact with store clerks to use the voucher and obtain items. They could provide a personal buyer service for people who have no time in their schedules to visit stores, especially for the higher-paying passenger and super-frequent fliers they wish to support.

Idea 3: Packing & Entering: Tips for Your Thinking Style

Here’s where we can create nuanced tips that may help people about to take a trip, especially in certain contexts like going to specific countries or traveling to locations experiencing certain weather. Considering that each person may be in a different thinking style for each trip, the team makes a set of four tones and intentions and pairs them with different contexts. The pairs of concepts combine to help people decide what to bring, or where to put a winter coat. (Onboard? Not if you’re landing at a regional airport with no jetway!) The tips cover how to parcel out baggage upon entering the airport. It’s directional and contextual. Any one human might be a “My Precious” on one flight, bringing a family heirloom to a newly married couple, and a “Hassle Drag” on the way home.

(These ideas are thanks to a team in my online course.)

The Outcome

The design team showed that on-time departure was correlated but not caused by the number of bags put in the overhead. The cause was related to other things (familiarity with the boarding process; how over-sold the flight was; the ratio of overhead space per passenger) they found in research. They not only managed to help the airline adjust the true causes of delays with other design approaches, but also helped passengers and airline employees see each other in a more human perspective.