Eat, Smell, Prey

exploring an example problem space

(See also the longer, hilarious video exploring interior cognition of both canine and feline fur people, and their interactions with the furless people.)

This case study aims to encourage you to get some problem-facing research started, using practical empathy and mental model diagrams. Researching the problem (as opposed to the solution) is a lot easier than you might suspect. So here’s the example: I studied how dogs maximize their experiences of the last day or two. (17-Oct-2024: updated datasheet and updated datasheet with neighborhoods)

Does the thought of analyzing a bunch of transcripts sound about as exciting as going home to the apartment after only 10 minutes in the park?

Or maybe the last time you did formal analysis, it left you feeling flat-out exhausted.

But you do admit, you ARE curious.

The knowledge you could gain through empathy research would be a spot of brightness in the cold wilderness of your org.

And sometimes it’s fun to get down and dirty with the details.

Especially when the data set isn’t too big and the patterns arrange themselves like a work of art.

So c’mon. Get the show on the road.

Let’s Play with an Example

To more easily focus on the steps, I’ve chosen content that is light-hearted: a look at the world inside a canine mind. I am focused on understanding the dogs’ approaches to their days, not on any particular solution for them. (That comes later.) For now I only pay attention to the dogs’ thinking as they maximized their experiences throughout the prior day or two.

This example details each step, as well as what to expect in terms of your time and your natural skills.

1. Decide What to Study This Time

Since this is my own round of research, I can choose my own scope and behavioral audience segment. You always pair a scope with an audience, because trying to study “everyone” is impossible, and studying too broad a scope doesn’t work. You want patterns to come out of the listening sessions, and this only happens after listening to at least 5 or 6 participants from the same behavioral segment about a particular intent they are pursuing. Otherwise, patterns do not materialize.

I want this to be a small study I can execute quickly, so I choose only one behavioral audience segment. The segment I choose is core members of the “family” who play a central role in the daily routine. And the dogs in this segment need big personalities (some would say “quirky”) to buoy up those daily habits. With ties this close, the people are much more likely to understand the dogs’ thinking and be able to write it down for me.

This is my first foray into the minds of dogs, so I want to map out the lay of the land. In later studies I will be able to dive into some of the things that I learn in this pass. I choose a scope exploring what went through a dog’s mind during the past day or two as they sought to make the most of each moment, especially as they interacted with their person. This scope can include other central people in the household.

Scope of research: What went through your mind this morning or yesterday as you went about your day and interacted with your person? (or yesterday or on a memorable day)

Behavioral audience segment: gregarious dogs who consider themselves core members of their human “pack”

Demographics: none (I assumed that none of these affect a dog’s thinking: age, gender, size, tail type, ear shape, fur style, location:rural/suburban/urban)

Participants: at least 5-6 dogs

Total duration: 10-15 hours, spread over several business days

Duration (this step): 30 minutes

2. Find Candidates & Qualify Them as Participants

I reach out on Twitter to find people whose dogs might qualify to participate in the study. I admit, this is much easier than trying to find eager candidates for some of my business clients. With dogs, it is also much easier to validate that the candidates are of the correct behavioral audience segment: a few emails back and forth with each person establishes whether their dog is, indeed, central to their life.

Unfortunately, because it is easy to find candidates, I end up with 12 participants! I worry that doubling the number of participants will make the study take too much time. But I decide to go for it.

Duration: fifteen minutes here and there, totaling maybe 2.5 hours.

Reality note: These two steps, finding candidates and qualifying them, normally take more work for professional studies. If you have set up a clear definition of the behavioral segments you’re looking for, though, it is really busy work, not thinky-think work. Nonetheless, busy work takes your attention. You will want to call each candidate whose contact information you’ve collected and conduct a five-minute chat to decide if they fit the behavioral audience segment and if they can tell a story. Telling a story is important; if it’s like pulling teeth to get the person to tell you a story, then you’ll need to thank them and disqualify them as a participant. Other roadblocks will crop up to slow down your progress. Sometimes I can’t even get enough candidates to indicate they’re interested. When this happens, I expand the channels I’m using to find people:

- sign-ups on my client’s websites

- tweets and emails to those in the industry or friends of those in the industry

- paid ads on sites or newsletters the candidates frequent

- maybe a recruiter if the candidates I’m after are likely to sign up with the recruiter to be picked for studies

- maybe my client’s own customer list, if those folks can talk about their intents not the product. And if they aren’t too pestered by your organization.

Avoid using an ad on a general-purpose public list, because, like folks who sign up with recruiters, these people are mainly after the extra money they can earn from stipends. And they are really good at telling fabrications in order to get those stipends.

3. Gather the Stories

For this study, I face the issue of not speaking the same language as the participants. I do what I would normally do: I teach interpreters to conduct the listening sessions and ask them to email me transcripts. In some transcripts I see concepts that were skipped over, where I want to dig deeper, so I reply to the interpreter, asking them to spend a little more time listening to the dog explain this deeper thinking. The interpreter then emails further answers in reply.

Duration: Collecting stories by email took about 3 hours, spread out over the course of several days.

Reality note: Actual listening sessions over the phone can run from 20-70 minutes each, and span one or two weeks. I always set aside 1.5 hours for each session, in order to prep myself, run the session, then review my understanding of what the participant was trying to convey to me. I often write several memory-based summaries right after the session. (See step #4.) I never run more than two listening sessions a day, lest I confuse the stories and ask about a concept mentioned by an earlier participant.

4. Summarize the Concepts

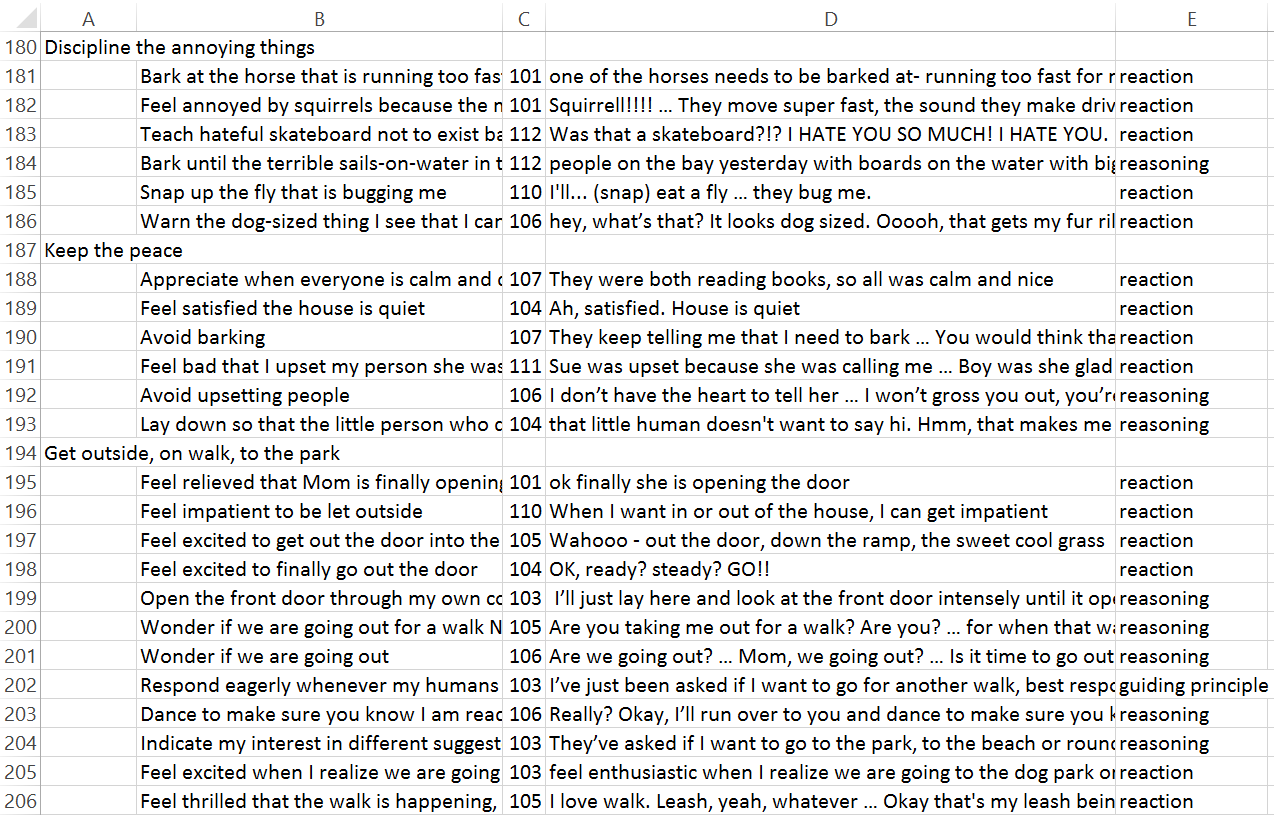

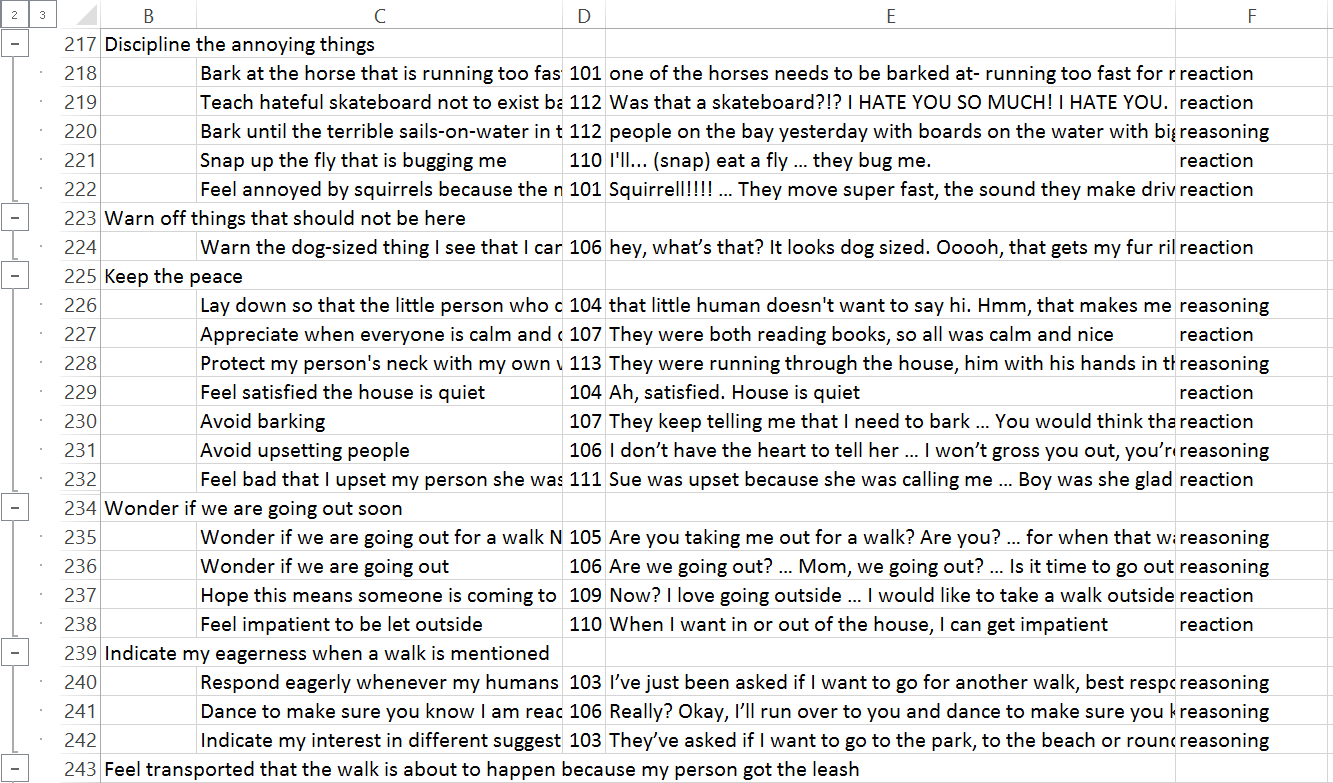

Next I comb through the transcripts for the three types of concepts that I always pull out: thinking/cognition, reaction/emotion, and guiding principle. These things appear with crystal clarity in the dogs’ transcripts–it turns out dogs are pretty straightforward and frank in the way they express their thoughts. For demonstration purposes, I mark these concepts in colors. Sometimes the concepts are woven through different parts of the transcript; sometimes they appear as a compact whole in one place.

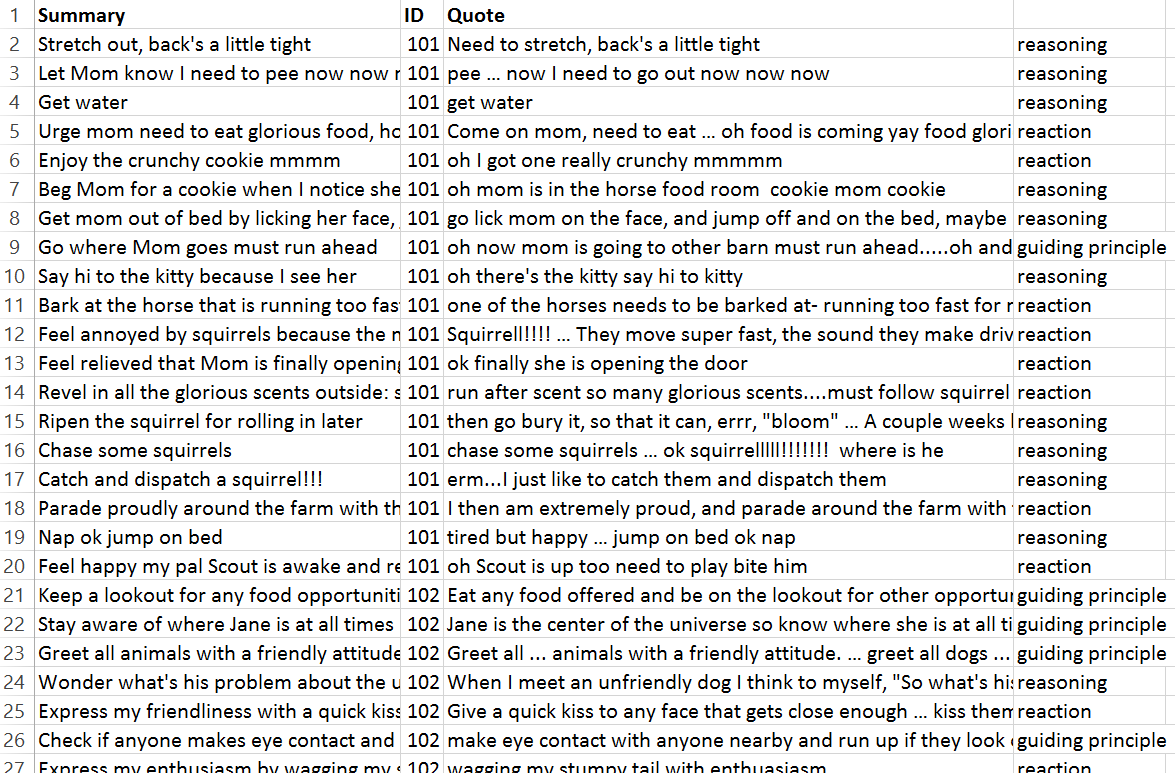

I copy each of these quotes into a list in a different document. (I prefer working digitally rather than writing on sticky notes, so I use a spreadsheet as my list-keeper.) I label each quote with an identifying number for the dog, so the participant’s name remains confidential–not that the dogs really care, but it’s my standard practice.

Each time I paste a quote in the list, I write a summary of it. The summary follows a particular format so that later I will be able to re-understand that quote more quickly when I seek to group it into a pattern. This format begins with a first-person present-tense verb, which also helps me get into the dog’s way of thinking.

Duration: In this case the emails were very short, so it took 15-30 minutes each, for a total of about 5 hours.

Reality note: Ordinarily it takes an experienced summary-writer about 3-4 hours to comb through a 16-page transcript (around an hour of listening in a session). I’ve seen rookies take 4-8 hours per transcript.

5. Group the Patterns

Once all the quotes and summaries are in the list, I begin pattern-hunting. This step really just comes down to scanning for the matching “tile” like in the childhood game–or like the Sesame Street(™) which-of-these-things-is-not-like-the-other game. But how the summaries match is important.

In the new two-part course on Qualitative Data Synthesis, I explain that the “affinity technique” we use here is not keyword or noun based. It’s not what someone, but what they were focused on accomplishing back at that moment. This is the affinity technique of “focus of mental attention.” I explain it deeply in the course.

Like some of the other affinity techniques, it’s emergent. It starts with a blank slate and the focuses of mental attention arise. It’s not top-down, where you have an idea what the groups might be as a researcher working in that particular org. A characteristic of emergent synthesis is that the groups that start building will change as you add more summaries. I also explain this deeply in the course.

The reason we do it this way is to resist our own bias, to let the true cognition of people shine through the patterns. In the end, it’s the patterns, not the summaries themselves, that our teams work with over the years.

You start with one concept that you believe will be easy to find matches for, then you run through all the summaries and gather up those matches. Then you select another concept and gather up the matches for that one. You keep doing this until all the concepts are in patterns or have been identified as standalone.

Important: I try not to label a pile of concepts until a few of them are in the pile. There are two reasons for this:

- I want to work from the bottom up, rather than specify labels in the beginning and add summaries to them. I work from the bottom up because this is inductive reasoning; you infer a pattern from a set of concepts, which means that pattern is probably correct, but not necessarily the only answer. If I specify labels in the beginning, I will end up generalizing or changing the nuance of some concepts in order to force them under that label.

- The initial piles will split up into smaller piles, or some concepts from one pile will merge with concepts from a different pile to form a new pile. I want to be willing to make these changes, to let this happen freely as I notice more nuanced affinities. I don’t want to force anything.

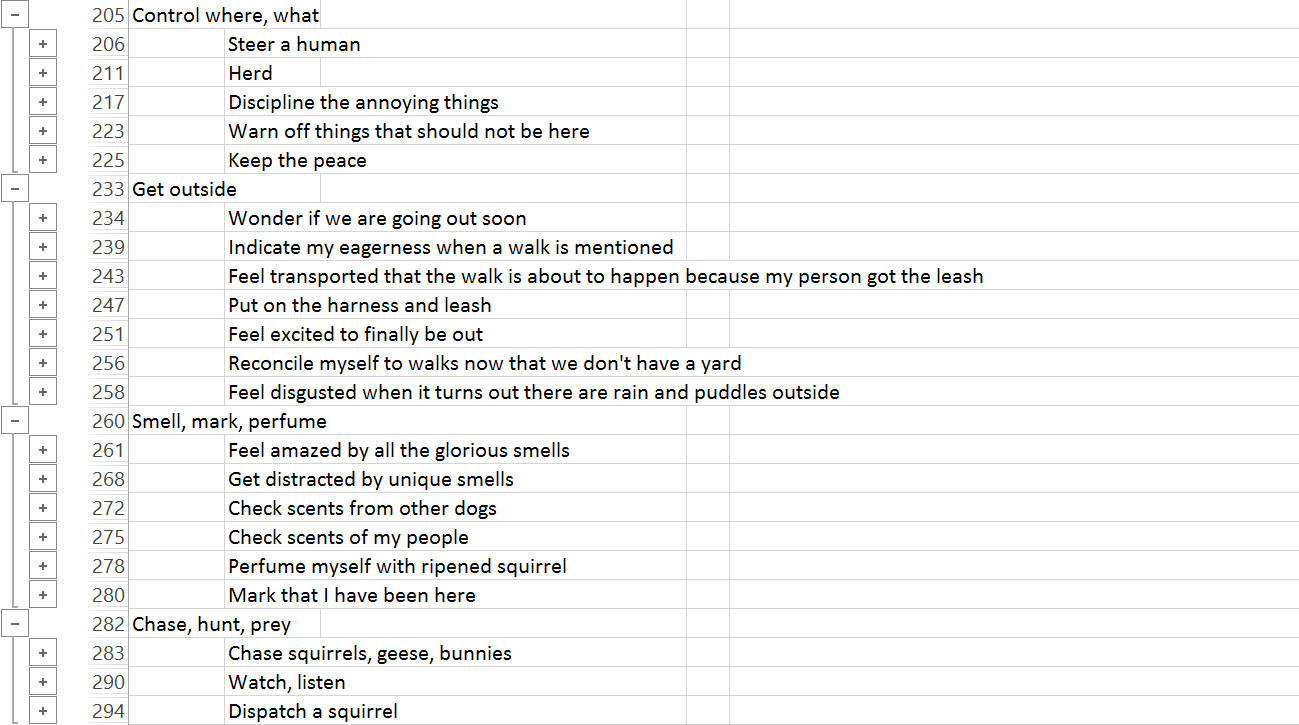

Finally, I sketch in a higher level of hierarchy–a group-of-groups level–based on affinity of different groups to one another. Labels for these higher level groups are derived from the collection of lower-level group labels. I do this to add structure, so that it’s easier for the human mind to find things later.

Duration: For the dogs, it went fast because the material was so … engaging. It took about 6 hours for all iterations of this step.

Reality note: Finding the patterns takes the most time of any step in the process. If you are experienced at this, it usually takes 3-4 hours on average per participant to find the patterns. It takes longer at the start, when you have no patterns yet, and then it goes faster.

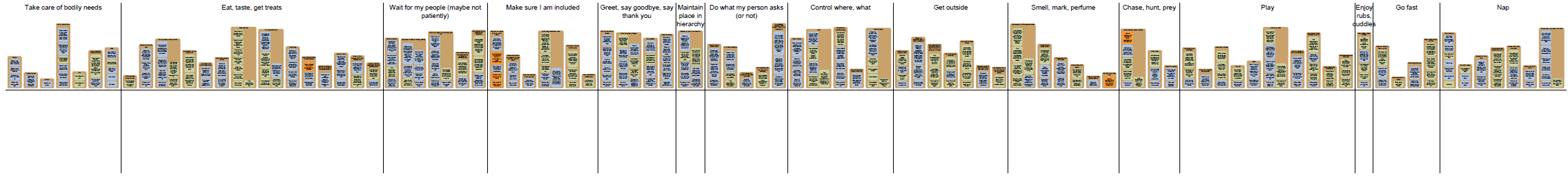

6. Create a Diagram (optional)

I want to use this data in my workshops, so participants can try out gap analysis and brainstorming support. So I need a visual diagram, which is more accessible than a spreadsheet for many people.

The diagram has a kind of artistic flow to the layout. It invites exploration. It also invites the addition of blocks below a certain tower that represent things your organization does in support of that tower. When you align the things you do, you can easily see gaps in how you support people … um, dogs … and you can consider whether those are gaps you’d like to address or not. If you want to address them, you can use the information in the towers to kick off brainstorming. And you can use the whole diagram as a roadmap for where you would like to focus over the next few years, as you extend and transform your offerings to better support how people (or dogs, in this case) are thinking.

Duration: Here the inverse happened. Instead of only taking an hour at most, it took me 5.5 hours to do everything: get the proper installation of the Python environment and Windows extension set up, download the script, and generate the diagram.

UPDATE: Now we have a mental model diagram generator here on this site! No more Python installs required.

7. Explore the Findings ← the fun part!

Now that I have the data organized, I take some time to pore over it. Dogs have some pretty obviously canine guiding principles. (Another way to think think of their guiding principles is “operating instructions for dogs.”) You can boil it down to “Eat, Smell, Prey.”

- Keep a lookout for any food opportunities

- Pee on anything that is new in my area, to mark that I have been here

- Chase things for the thrill of it

There is an emphasis on waiting for the humans. Waiting and waiting … not necessarily with patience.

- Get human to notice by staring, whining

- Wake up human

- Stay near my person, so I’m ready to be part of things

- Wait for people to do this thing with me

- Feel confused that we were going out, but now we’re not

- Feel frustrated that my people are slow, forget things

The behavior that surprises me was the canine control freak aspect. I thought dogs were laid back, but apparently not always.

- Warn off things that should not be here

- Discipline the annoying things

- Keep the peace

- Herd, Steer

There is also the importance of going fast, in any form. Speed is an elixir!

- Look forward to a presumed car ride

- Go fast in a car!

- Go fast on a bike cart!

- Go fast running!

- Watch things blur past

- Enjoy the wind on my face

And of course there are the expected doggie things.

- Get outside

- Take care of bodily needs

- Play

- Nap

As far as mapping an organization’s efforts in support of dogs, over time my workshop attendees will come up with more and more ideas. Each idea is based on a situation and organization that the participant team dreams up in the hour they have for the exercise. If you curate a similar diagram (or set of diagrams) specific to your organization, then your product strategy can be informed by this roadmap.

Duration: 1.25 hours

8. Decide What to Study Next

The next study I will do depends on my goals. If I am a pet psychologist, I might be interested in diving into the control freak area more deeply. If I am trying to entertain dogs in a new fashion, I might latch onto the Go Fast area to see what additional thinking I can uncover. It’s all guided by what the organization is up to and interested in.

The timing of the next study will be predicated by the need for the information. If I am going to be making some decisions in the immediate future, I need to start the next study pronto. But if the decisions aren’t going to happen until later, I can wait.

Duration: 15 minutes

Total duration: 24 hours (because of the 12 participants, instead of 6)

In the meantime, I have some patterns that are helpful to being able to channel a dog’s mind and heart. Because all the findings were written with first-person verbs, it is easy to apply empathy by stepping into their shoes … I mean paws. Hopefully this example helps you feel energetic and gleeful about indulging your research curiosity before zeroing in on solutions.